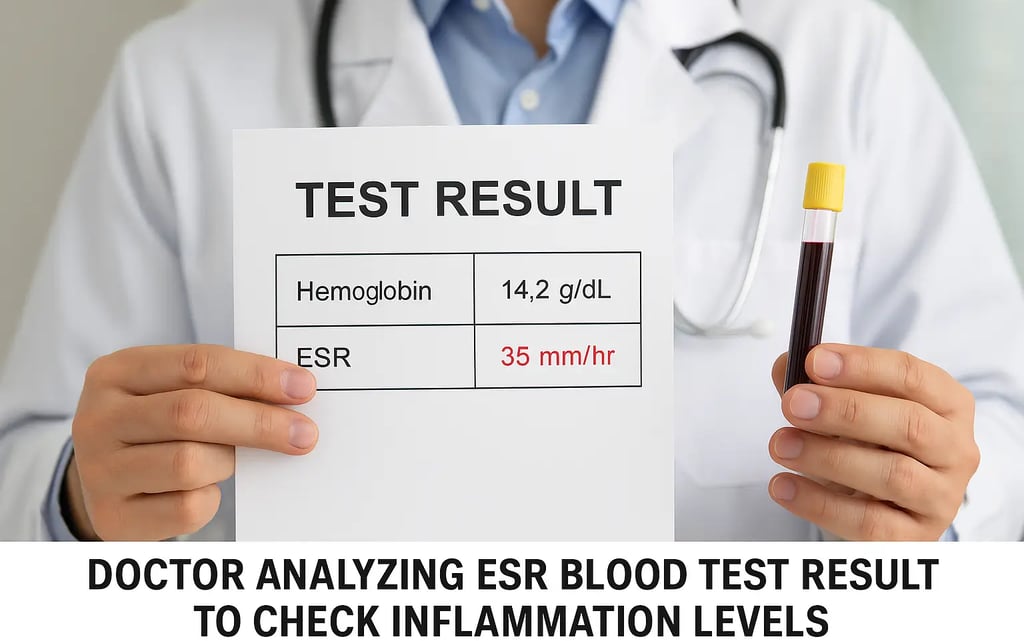

What is ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate)? Meaning, Normal Range, Test, and Interpretation

Discover everything about the ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate) test—its purpose, normal range, testing methods, interpretation, and clinical significance in detecting inflammation and disease.

What is Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)?

The Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) is a common blood test used to detect inflammation in the body. It measures the rate at which red blood cells (RBCs) settle at the bottom of a test tube over one hour. The test is based on the principle that inflammatory proteins in the blood, such as fibrinogen, cause RBCs to clump together and settle more rapidly.

A high ESR level may indicate the presence of infections, autoimmune diseases, or chronic inflammatory conditions, whereas a normal ESR often rules out significant inflammation. However, ESR is considered a non-specific test, meaning it doesn’t point to a specific disease but signals the need for further investigation.

Why is the ESR Test Important?

The ESR test plays a vital role in clinical diagnostics by serving as an early marker of inflammation. It helps physicians assess the presence and severity of conditions such as:

Autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus)

Chronic infections (e.g., tuberculosis, endocarditis)

Cancers and malignancies

Inflammatory bowel diseases (e.g., Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis)

It is often used in monitoring disease progression or evaluating treatment effectiveness. For example, a rising ESR might indicate worsening disease activity, while a decreasing ESR can show response to treatment.

Despite its value, the ESR is typically used in conjunction with other diagnostic tools, such as CRP (C-reactive protein), antibody testing, and imaging studies to make an accurate diagnosis.

How is the ESR Test Performed?

Testing Methods:

There are two standard methods to perform an ESR test:

Westergren Method

Most widely used

Blood is mixed with anticoagulant and placed in a tall tube

RBC fall rate is measured after one hour

Wintrobe Method

Uses a shorter, narrower tube

Slightly less sensitive than the Westergren method

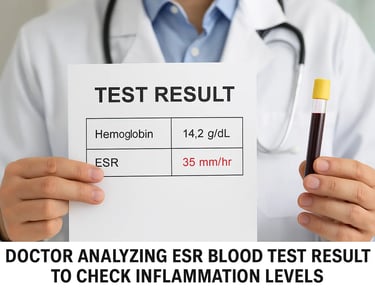

Normal ESR Ranges:

Men: Up to 15 mm/hr

Women: Up to 20 mm/hr (can increase slightly with age)

Older Adults: Slightly higher values are common

Children: Typically lower ESR values

Elevated ESR results require careful clinical correlation, as many factors can influence these numbers.

How to Interpret ESR Results

Interpreting ESR levels requires context and clinical expertise. Here’s what different ESR levels may suggest:

Elevated ESR:

Infections (e.g., pneumonia, UTI)

Autoimmune conditions (e.g., lupus, rheumatoid arthritis)

Chronic inflammation (e.g., vasculitis, sarcoidosis)

Certain cancers

Low ESR:

Polycythemia vera

Sickle cell anemia

Congestive heart failure

High white blood cell counts or abnormal red cell shapes

Other influencing factors include pregnancy, anemia, aging, obesity, and certain medications.

Limitations of ESR Testing

While useful, the ESR test has several limitations:

Non-Specific: Cannot identify the exact cause of inflammation

Easily Affected by External Factors: Age, gender, anemia, and even diet can affect results

Slow to Change: ESR levels may take time to rise or fall, making it less suitable for real-time monitoring compared to CRP

For these reasons, doctors often pair ESR with complementary diagnostic tools to arrive at a conclusive diagnosis.

Conclusion

The Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) is a simple yet powerful blood test that provides insights into underlying inflammation or disease activity. Although it’s not a standalone diagnostic tool, ESR plays a critical role in screening, diagnosing, and monitoring inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

To make the most of ESR testing, always consider it in combination with other lab tests and clinical assessments. Regular monitoring and proper interpretation can guide timely treatment and better patient outcomes.