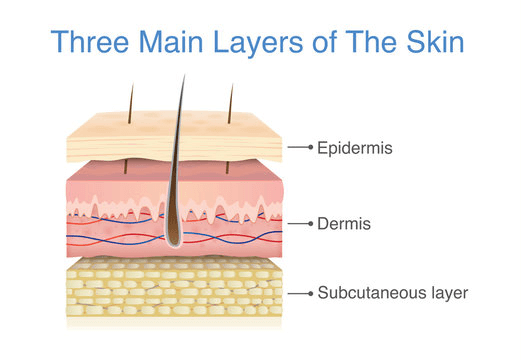

Layers of Our Skin: A Deep Dive into Skin Layers

Explore the intricate biology of skin layers and gain a deeper understanding of how our skin functions. Dive into the layers of the skin to uncover its complexities.

The Epidermis: Our Protective Shield

The epidermis is the outermost layer of our skin, acting as the primary barrier against various environmental factors such as bacteria, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and pollutants. This layer is composed of multiple sub-layers, each serving distinct functions essential for skin health and protection.

At the surface of the epidermis lies the stratum corneum, which consists of dead keratinocytes that have migrated from the deeper layers. These cells are continuously shed and replaced, forming a tough, protective barrier. Just below the stratum corneum is the stratum granulosum, where keratinocytes begin to die and form a waterproof barrier. Further in, the stratum spinosum provides structural support and strength, while the basal layer, also known as the stratum basale, is the deepest sub-layer where new keratinocyte cells are generated.

Keratinocytes are the predominant cell type in the epidermis, responsible for producing keratin, a protein that strengthens the skin. These cells play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of the skin barrier. Another vital cell type is the melanocyte, located in the basal layer, which produces melanin, the pigment responsible for skin color. Melanin also offers protection against UV radiation by absorbing and dissipating harmful rays.

Langerhans cells, found in the stratum spinosum, are part of the immune system. They detect and process microbial invaders and present them to other immune cells, initiating an immune response to protect the body from infections.

The epidermis undergoes a continuous process of cell turnover, where new cells are formed in the basal layer and gradually move up to the stratum corneum before being shed. This process ensures that the skin remains resilient and capable of protecting the body. Proper skincare, including hydration and the use of sunscreen, is essential for maintaining a healthy epidermis, as it supports the skin’s natural functions and enhances its protective capabilities.

The Dermis: The Supportive Middle Layer

The dermis, situated beneath the epidermis, is a robust and thicker layer that plays a crucial role in maintaining the skin's structural integrity and elasticity. Predominantly composed of collagen and elastin fibers, the dermis provides the necessary support and flexibility, ensuring the skin's resilience and durability. Collagen fibers offer tensile strength, while elastin fibers allow the skin to return to its original shape after stretching or contracting, contributing to the overall elasticity of the skin.

Integral to the dermis are blood vessels, which supply essential nutrients and oxygen to the epidermis, promoting healthy skin function and regeneration. These blood vessels also play a significant role in thermoregulation, helping to maintain the body's temperature by dilating or constricting in response to temperature changes. Nerves within the dermis are responsible for the sensation of touch, pain, and temperature, enabling the skin to act as a sensory organ.

Additionally, the dermis houses various glands, including sebaceous glands that produce sebum—an oily substance that lubricates and waterproofs the skin—and sweat glands that aid in cooling the body through perspiration. The interaction between fibroblasts and the extracellular matrix is vital for maintaining the dermis's health and function. Fibroblasts are responsible for producing collagen and elastin, contributing to the skin's repair and resilience.

Common issues that affect the dermis include wrinkles and stretch marks. Wrinkles form due to the breakdown of collagen and elastin fibers, often accelerated by aging, UV exposure, and lifestyle factors. Stretch marks occur when the skin is overstretched, leading to the tearing of the dermis and the formation of scar tissue. Preventive measures such as protecting the skin from excessive sun exposure, maintaining hydration, and using skincare products that promote collagen production can help mitigate these issues.

The Hypodermis: The Deepest Layer

The hypodermis, also referred to as the subcutaneous layer, represents the deepest section of the skin. It is primarily composed of adipocytes, or fat cells, alongside connective tissue. This layer plays a crucial role in the body's insulation, cushioning, and energy storage mechanisms. Adipocytes within the hypodermis store energy in the form of fat, contributing significantly to the body's energy balance and metabolism.

One of the primary functions of the hypodermis is to provide insulation, which helps regulate body temperature by reducing heat loss. The cushioning effect of the hypodermis protects underlying muscles and bones from external impacts, thereby preventing injuries. Moreover, the fat stored in the hypodermis serves as an energy reserve that the body can utilize during times of caloric deficit.

The composition of the hypodermis varies across different parts of the body and among individuals. Factors such as genetics, diet, and lifestyle influence the distribution and quantity of adipose tissue. This variation contributes to the diversity in body contours and shapes among individuals. The connective tissue within the hypodermis also plays a pivotal role in anchoring the skin to underlying structures, ensuring skin stability and elasticity.

Interaction between the hypodermis and the overlying skin layers is essential for maintaining overall skin health. The hypodermis supplies nutrients to the dermis and epidermis, supporting their functions and promoting skin repair and regeneration. Additionally, the hypodermis acts as a conduit for larger blood vessels and nerves that extend into the dermis, facilitating essential physiological processes.

Weight fluctuations and aging can significantly impact the hypodermis. During weight gain, the expansion of adipocytes leads to increased subcutaneous fat, altering body contours. Conversely, weight loss can result in the reduction of adipose tissue, affecting the skin's structural support and potentially leading to sagging. Aging naturally diminishes the thickness of the hypodermis, reducing its cushioning capacity and contributing to thinner, more fragile skin.